[Intro to Computational Thinking] Introduction to Computational Thinking via Simulation with R

“What I cannot create, I do not understand” – Richard Feynman

“It is immoral to collect data before simulating the hypothesized data generating process.” – Andrew Gelman (what I remember of a comment to the Stanford Causal Inference Seminar in 2020).

# Load required packages

xfun::pkg_attach2("DiagrammeR")📝 Lesson Preview

Throughout, we will include examples of how to plot with base R and ggplot2

Motivation: Why simulate?

We’ve covered the basics of programming in R. Let’s bring many of these concepts together to help us better understand our research problems, even before we gather any data. To do this, we’ll learn how to use R to simulate and analyse data generating processes (DGP).

A data generating process is the process that creates the data in a data set. These processes can include, for example, both the social processes that result in migration data and even unexpected (or undesired) issues in the sampling procedure like non-random study attrition.

Why are we talking about simulating data generating processes in an introduction to R course? There are two sets of reasons.

First, computational generative modeling–simulating data generating processes with a computer–is a useful tool for understanding and evaluating the statistical methods you are using to study data generating processes (Gelman, Hill, and Vehtari 2021, 76). Will your chosen statistical model identify the effect you are interested, even if you completely understand the DGP? This is surprisingly often not the case, especially for non-trivial data generating processes. Simulation allows you to stress test your models, with a given assumed DGP, and compare the appropriateness of different models for this DGP.

In Gelman’s strong view stated above, if your identification strategy can’t recover effects in known–simulated data–you shouldn’t waste time and money collecting real world data. If data gathering is time consuming and expensive, you can also use generative modelling to make progress on your problem before your data is fully collected.

The second reason we are covering statistical simulation, and most importantly for this class, is that simulation requires you to work your new R programmering skills. The DGP we will work with are probabilistic. You need to repeat the simulations with the same data generating process multiple times to understand its statistical properties. This is called the Monte Carlo Method. You should never do this repeated sampling by rewriting the same function over and over. Instead, encode the sampling in a function that you can run repeatedly and, ideally, efficiently, e.g. in parallel.

Simple simulation workflow

This is a typical simulation workflow:

We start by hypothesizing what the data generating process we care about might be. Then we propose one or more candidate strategies to identify effects in this data generating process, e.g. regression, matching, difference in differences. We begin implementing the simulation for the DGP-identification strategy by creating function(s) for simulating and analyzing the data for one simulation draw. Once we have the simulation correctly working for one draw, we create a function(s) to make \(n\) additional draws. We then (usually) examine the results by plotting quantities of interest from the simulations. Quantities of interest could be the distribution of some estimate we are interested in or the error from some “ground truth” across simulations. Frequently, we learn something unexpected by the end of this process. Our learnings could include a new understanding of the data generating process or our candidate identification strategies. Because we often learn something about how our originally selected identification strategy is lacking or our proposed DGP is too simplistic, we often need to repeat the process a number of times before we are confident we understand even the simulated data and its hypothetical relationship to the real social phenomenon we are interested in.

Notice that most steps can involve some debugging. We’ll dig into debugging below. But let’s look at a simple ideal case first.

Example 1: Simple A/B Test Discrete probabilities

Imagine that we want to run an A/B test–randomised control trial–to evaluate the causal effect of a new treatment relative to the status quo control counterfactual. We are interested in the effect of the treatment on whether or not individuals in the study do some action–e.g. vote in an election.1 Imagine the outcome is a discrete variable coded \([0, 1]\). Can we use a difference of means test to estimate the treatment effect?

Let’s start by hypothesizing what the data generating process could be. Imagine that based on prior research we know that there is a baseline probability of the outcome being \(1\) when a person is exposed to the control of 0.1, i.e.:

\[Y \sim \mathrm{Binomial}(0.1)\] To simulate one draw from this binomial distribution in R use:

control_y_1 <- rbinom(n = 1, size = 1, prob = 0.1)

control_y_1## [1] 0Let’s walk through this code. rbinom() is the function to randomly (the r in rbinom) draw from the binomial distribution (binom). n is the number of draws for this simulation, size is the “number of trials”. Basically it means that you want the “success” outcome to be 1 and 0 otherwise. prob is the probability of “success”.

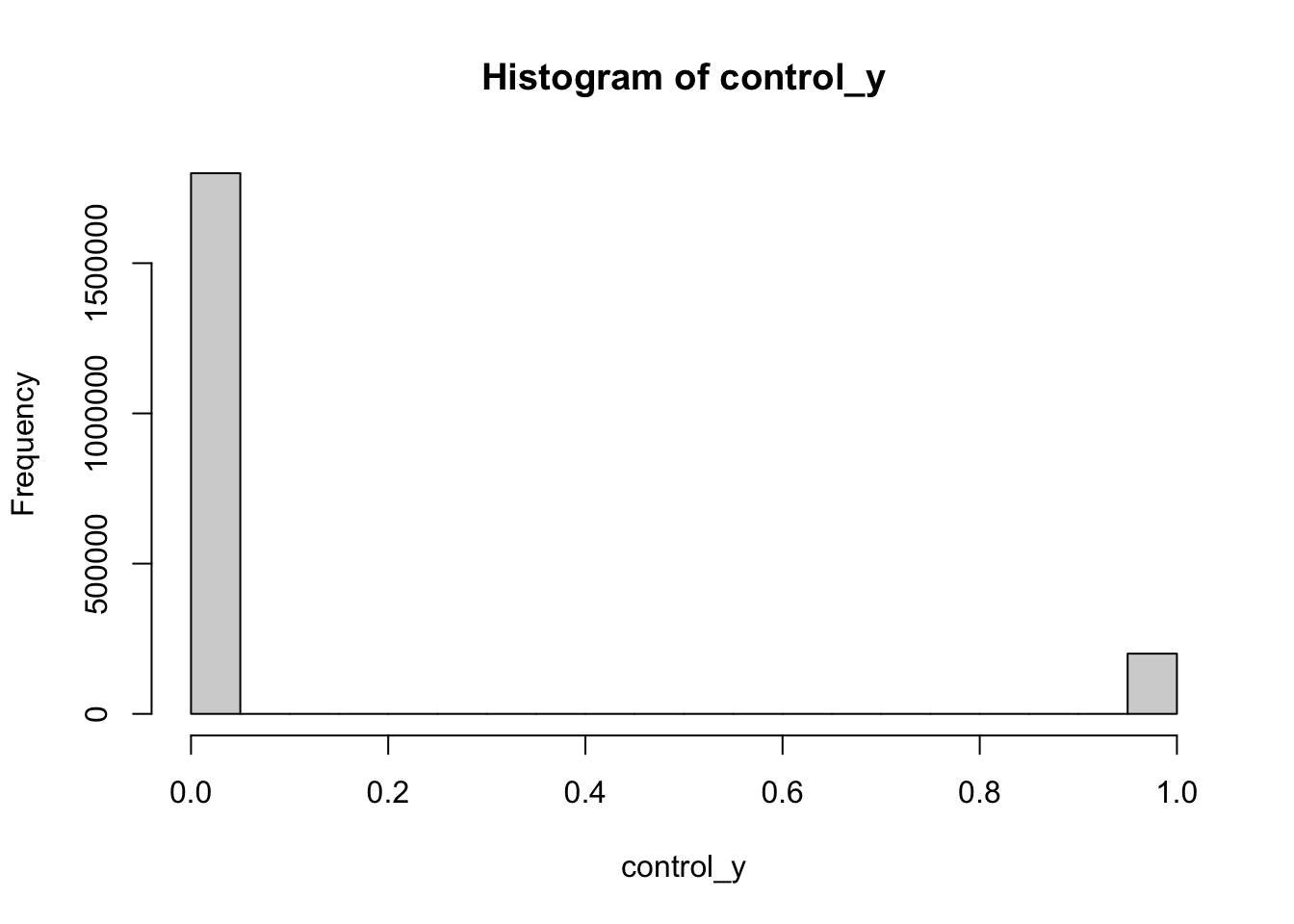

It’s unlikely that we will run an A/B test with only one participant in the control group (this would be hilariously under-powered). So, let’s simulate a test with 2,000,000 draws2 and plot the results.

# number of observations variable to ensure consistency across sims

n_obs <- 2e6

control_prob <- 0.1

control_y <- rbinom(n = n_obs, size = 1, prob = control_prob)

hist(control_y)

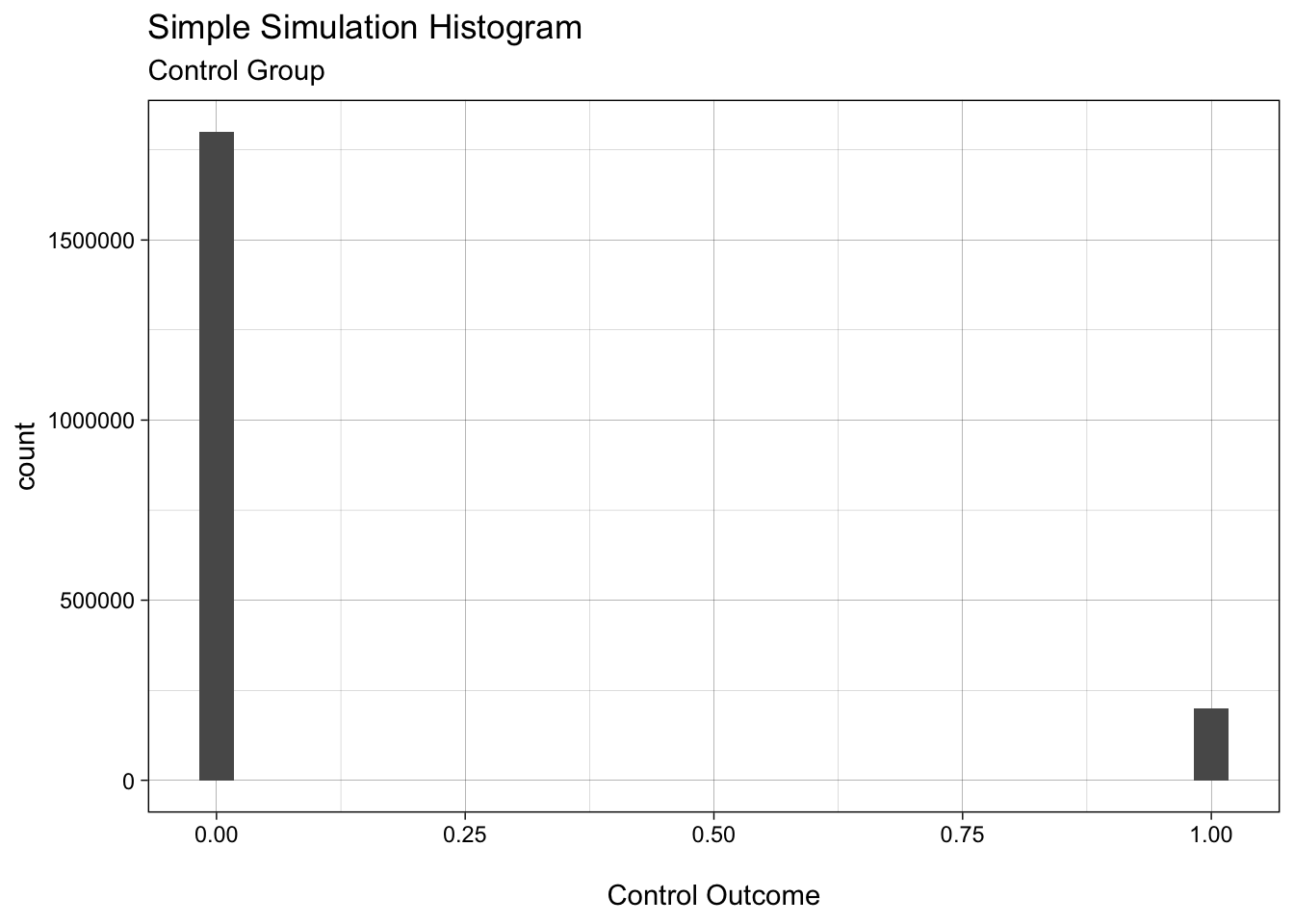

Side note: Histograms with ggplot2

ggplot2 is a very powerful way to create graphics in R. Here is an example of how you would create a histogram with ggplot2.

# ggplot2 is a member of the "tidyverse" set of packages

xfun::pkg_attach2("tidyverse")

# I personally enjoy the simplicity of the "linedraw" theme

theme_set(theme_linedraw())

# ggplot cannot accept a vector, like `hist`

# You need to convert to a data frame or the tidyverse equivalent "tibble"

control_y_tbl <- as_tibble(control_y)

# Plot and change the x-axis label

ggplot(control_y_tbl, aes(x = value)) + # as_tibble names the column "value" by default

geom_histogram() +

xlab("\nControl Outcome") + # \n adds a line break before the label

ggtitle("Simple Simulation Histogram", subtitle = "Control Group")

Notice how you build up the layers of the plot in ggplot by adding “geoms” with plus (+) notation. These are literally stacked on top of each other in the order you enter them in code. So the base layer is set with ggplot. This specifies the data frame to work with and the aesthetics (aes) layer that defines things like the X and Y coordinates, and grouping variables. Histograms only need the x-axis specified in aes because the y-axis will be the automatically generated count per histogram bin. But for other geoms, such as geom_point for scatter plots, you also need to specify a variable that defines the y-axis with the y argument.

If you plan to make similar ggplot plots multiple times, consider wrapping it in a function. For example:

# @param outcomes numeric vector

# @param subtitle character string of the plot's subtitle

plot_histogram <- function(outcomes, subtitle) {

if (missing(subtitle)) stop("subtitle must be specified")

x_tbl <- as_tibble(outcomes)

ggplot(x_tbl, aes(x = value)) +

geom_histogram() +

xlab("\nControl Outcome") +

ggtitle("Simple Simulation Histogram", subtitle = subtitle)

}

plot_histogram(outcomes = control_y, subtitle = "Control Group")

Ok, we’ve simulated one run of the control group. Now let’s think about the treatment group. Imagine we anticipate that a realistic effect of the treatment–again based on prior knowledge–is an average relative improvement of 1%. We simulate this with:

rel_effect <- 0.01

treat_prob <- control_prob + (control_prob * rel_effect)

treatment_y <- rbinom(n = n_obs, size = 1, prob = treat_prob)

plot_histogram(treatment_y, subtitle = "Treatment Group")

Finally, we compare the means of the two groups:

mean(treatment_y) - mean(control_y) ## [1] 0.0006515That’s one simulation. Let’s wrap it up in a function so it will be easy to run \(n\) simulations

# @param n integer number of draws per treatment arm

# @param control_prob numeric probability of control success [0, 1]

# @param rel_effect numeric relative effect, change in success probability

# caused by treatment

one_sim <- function(n, control_prob, rel_effect) {

treat_prob <- control_prob + (control_prob * rel_effect)

cy <- rbinom(n = n, size = 1, prob = control_prob)

ty <- rbinom(n = n, size = 1, prob = treat_prob)

mean(ty) - mean(cy)

}Let’s test it to make sure it works.

one_sim(n = n_obs, control_prob = control_prob,

rel_effect = rel_effect)## [1] 0.0005305This is very close to the true increase absolute of 0.001 (i.e. 1% of the control_prob of 0.1).

Side note: Documenting Functions in R

It is important to get in the habit of documenting your functions as you write them. This makes them easier for others (and yourself in the future) to understand.

There are some R documentation conventions to follow.3 Function documentation begins with a description of what the function does. Then each function parameter is documented using @param. It is not required, but it is good practice to document the expected type of the value for each argument, e.g. integer. You can also give examples of the function working with @examples. All of the documentation should be commented out with #'. E.g.

#' Simulate one A/B test outcome from the binomial distribution

#' and return the difference of the means of the two treatment arms.

#'

#' @param n integer number of observations per treatment arm

#' @param control_prob numeric probability of success in the control group

#' @param rel_effect numeric relative effect of the treatment compared

#' to the control

one_sim <- function(n, control_prob, rel_effect) {

treat_prob <- control_prob + (control_prob * rel_effect)

cy <- rbinom(n = n, size = 1, prob = control_prob)

ty <- rbinom(n = n, size = 1, prob = treat_prob)

mean(ty) - mean(cy)

}Monte Carlo with for

Now that we’ve created a function for one total draw of the simulated A/B test, let’s repeatedly sample it so that we can better understand the probabilistic properties of our hypothesized data generating process.

One way to do this is with for loops. For example:

# package to add a progress bar to monitor loop progress

xfun::pkg_attach2("progress")

# Create vector of NAs to take the simulation results

n_sims <- 100

mean_diff <- rep(NA, n_sims)

pb <- progress_bar$new(total = n_sims)

for (i in seq_along(mean_diff)) {

pb$tick() # increment the progress bar

mean_diff[i] <- one_sim(n = n_obs, control_prob = control_prob,

rel_effect = rel_effect)

#if (is.na(mean_diff[i])) stop(paste(i, "is missing"))

}

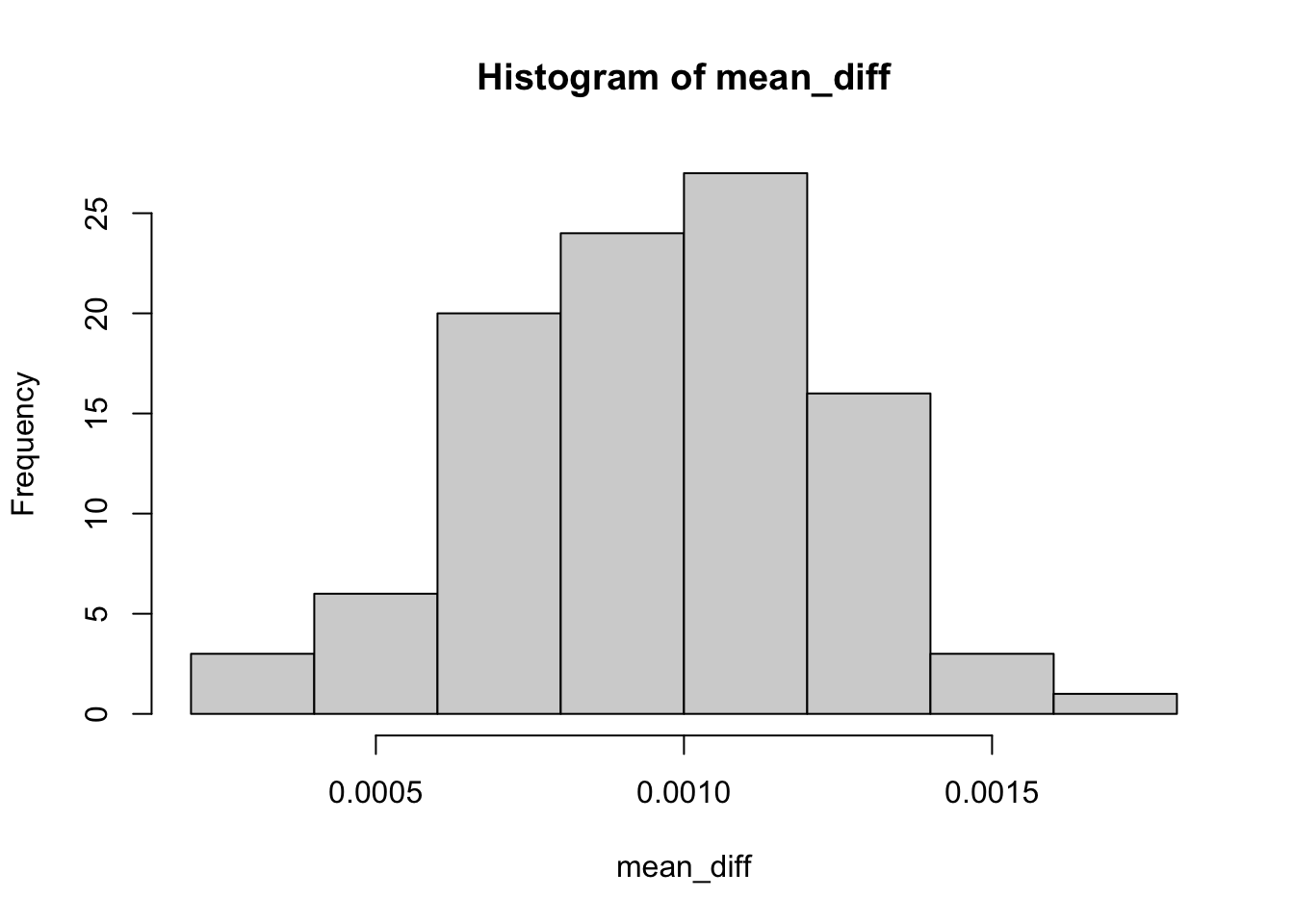

hist(mean_diff)

Monte Carlo with apply and parallelization

for loops are notoriously slow in R.4 This isn’t a problem if you are only doing a few simulations, but gets very tedious if you need to run many simulations. Often–though not always–using the apply family of functions is faster. They also can make it easier to parallelize your code.

Since we want to run the same function n times, we can use the replicate() helper function for the apply family:5

system.time(

mean_diff <- replicate(n_sims, one_sim(n = n_obs,

control_prob = control_prob,

rel_effect = rel_effect))

)## user system elapsed

## 5.695 0.135 5.834I wrapped this call in system.time() so that we can keep track of how much computation time we spend on the call. Monte Carlo simulations are just doing the same thing over and over. This computation time can add up.

We can see that the the apply version (above) in this case is pretty much as slow as the for loop (below).6

system.time(

for (i in seq_along(mean_diff)) {

mean_diff[i] <- one_sim(n = n_obs, control_prob = control_prob,

rel_effect = rel_effect)

}

)## user system elapsed

## 5.682 0.140 5.826So far we have been running all of our simulations in sequence. However, each simulation, by construction, is independent of the others. This is a perfect use case for parallelization.

There is a mc_replicate() helper function (originally from the rethinking package) that makes this easy for the code we have written so far.

xfun::pkg_attach2("mcreplicate")

system.time(

mc_replicate(n_sims, one_sim(n = n_obs,

control_prob = control_prob,

rel_effect = rel_effect),

mc.cores = 4)

)## user system elapsed

## 4.681 0.159 1.660As we would expect from running the simulations across 4 rather than one core, the elapsed time is faster with mc_replicate(). Note it is not 4 times faster in this case, because there is overhead in setting up the parallelization. With more samples we the overhead as a proportion of total computation time will decrease and we will approach 4x computation time.

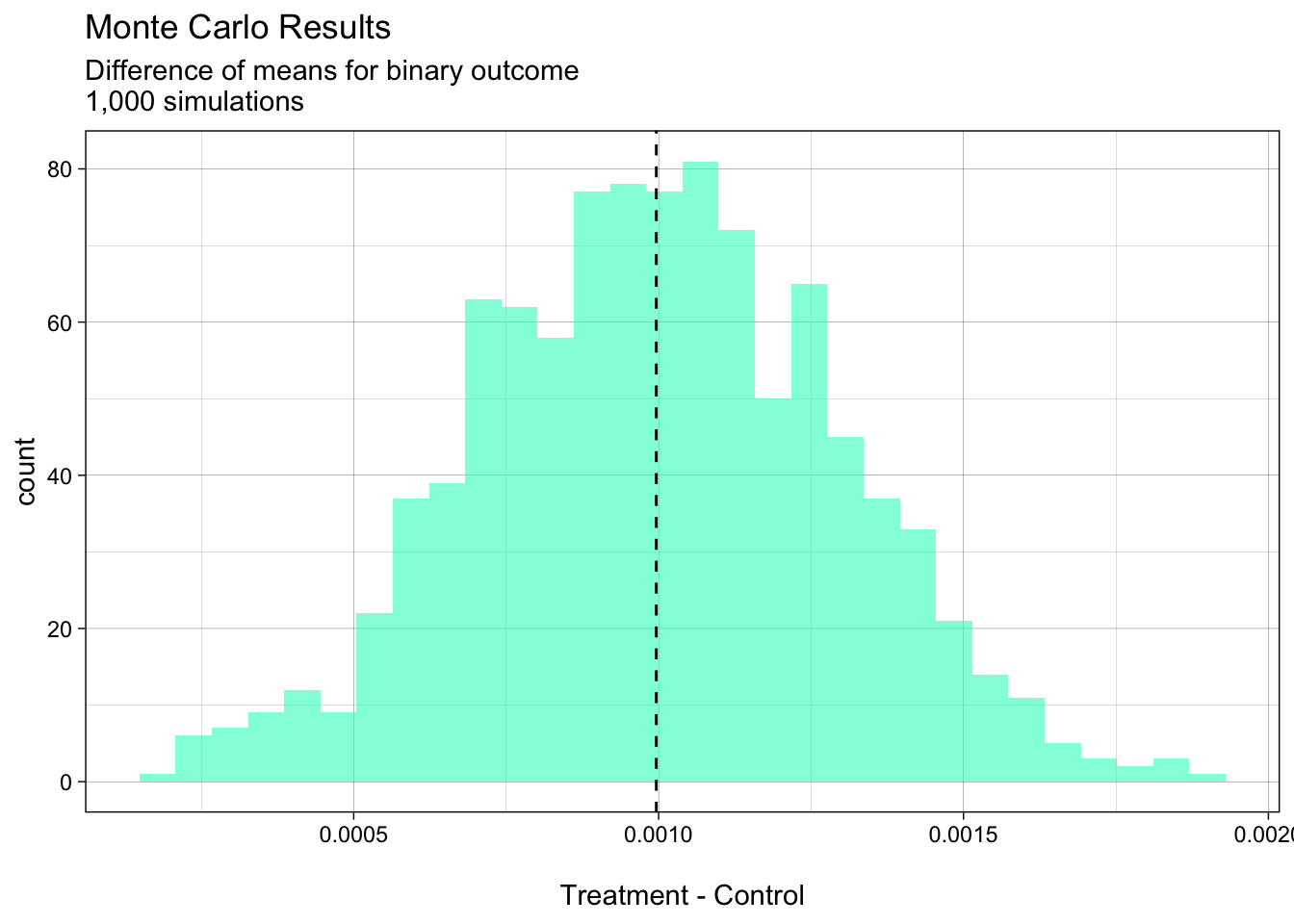

Finally, let’s see if the difference of means is a useful way of estimating the treatment effect for a binary outcome? Let’s run a few more simulations. We should see normally distributed difference of means centered on 0.001:

diff_means_1000 <- mc_replicate(1e3, one_sim(n = n_obs,

control_prob = control_prob,

rel_effect = rel_effect),

mc.cores = 4)# find mean of all simulations for plotting

mean_of_means <- mean(diff_means_1000)

# plot simulations with line at mean value

diff_means_1000_tbl <- as_tibble(diff_means_1000)

ggplot(diff_means_1000_tbl, aes(value)) +

geom_histogram(alpha = 0.6, fill = "#29ffc6") +

geom_vline(xintercept = mean_of_means, linetype = "dashed") +

xlab("\nTreatment - Control") +

ggtitle("Monte Carlo Results",

subtitle = "Difference of means for binary outcome\n1,000 simulations")

In this example, the more simulations we run, the more smooth and “normal” the curve will become.

Debugging in R

Debugging is the process of finding and resolving discrepancies between a program’s specification and its implementation.7 For example, I want a ggplot2 to plot multiple time series on the same plot as separate lines, but it plots them all as one–very jagged and confusing line. I could use a debugging process to find the cause of and correct this discrepancy.

The reason we are covering debugging now, is that statistical simulations are more complex computational and coding processes than we’ve seen before, so debugging them is more complicated.

Being mindful of your feelings

We’ll cover the the technical debugging tools available in R. But I first want to first mention a crucial part of effective (and less stressful) debugging: being mindful of your feelings about the bug.

A bug is frustrating. Our first encounter with a bug is an experience of disassociation between how we think the world should work and how it is working. It’s as if we want to put a plate in the cupboard, but each time we try to put the plate in the cupboard it flies out. Frustration inclines us to look for the cause of a bug in–almost always–the wrong place: “the stupid computer is broken”.

The best way to resolve bugs, as we’ll see, is to create testable hypotheses about what could be causing the bug. “The stupid computer is broken” is vague and so not a testable hypothesis.

So, it is crucial that when you find a bug, to take a step back and ask:

how does this bug make me feel?

If the answer is “angry, I want to throw my computer out the window”, your best next step is to take a break. Grab a tea or whatever. Then, with a piece of paper (or some other tool that gets you away from the temptation to just begin slamming out code on your keyboard) write down hypotheses about the cause of the bug and ways to test them.

Unlike social phenomena, many computer bugs are deterministic. The cause of a bug will usually cause the bug. So your chances of definitively finding the bug are high with the following process and tools.

Clear and testable program specifications

Finding your bug is a process of confirming the many things that you believe are true — until you find one which is not true.

—Norm Matloff (quote from Advanced R)

Great debugging is driven by having great expectations of what the program should return. Having a well defined expectation of what a program should do is important to knowing if you have a bug to begin with. One way to approach software development is to write tests for a function before you write the function. This is called test driven development.

Both in your functions, to test incremental expectations, and for the output of your functions you include automated tests. Here is a silly example. Imagine that we have a function that should add 2 + 2 and then divide by 2 to return 2. We can create an automated test like this:

# Function to test

two <- function() {

four <- 2 + 2

if (four != 4)

stop("Did not add 2 + 2 correctly")

four / 2

}

# Automated test

if (two() != 2) stop("function two did not return two")The if . . . stop statements automatically test whether or not the function is executing correctly. If there is a problem, the tests should help us pinpoint the cause more quickly.

Automated tests will also help us make sure that our code is correct even as we change it, for example, to add new features.

browser() for testing and dissecting

A key debugging R tool is the browser() function. When R executes some code and hits browser() it stops the execution and begins an interactive Browse mode. This allows you to explore objects created in the code execution in the environment that created then, as well as run new code. RStudio works really well with this function.

Imagine we wrote the loop above incorrectly:

one_sim_bug <- function(n, control_prob, rel_effect) {

treat_prob <- control_prob / (control_prob * rel_effect)

cy <- rbinom(n = n, size = 1, prob = control_prob)

ty <- rbinom(n = n, size = 1, prob = treat_prob)

mean(ty) - mean(cy)

}

mean_diff_bug <- rep(NA, n_sims)

for (i in seq_along(mean_diff)) {

mean_diff_bug[u] <- one_sim_bug(n = n_obs,

control_prob = control_prob,

rel_effect = rel_effect)

}We have two layers of nested functions where the bug could be. Let’s systematically use browser() to identify the source. Start from the outer most function–the for loop and work you way down as necessary.

for (i in seq_along(mean_diff)) {

browser()

mean_diff_bug[u] <- one_sim_bug(n = n_obs,

control_prob = control_prob,

rel_effect = rel_effect)

}Ok, we’ve found the typo. We should have used i instead of u to index the output of one_sim. To leave the browser environment type c + Enter (or on some Windows machines Q + Enter). Are we done? We’ll let’s check the output:

for (i in seq_along(mean_diff)) {

mean_diff_bug[i] <- one_sim_bug(n = n_obs,

control_prob = control_prob,

rel_effect = rel_effect)

}

hist(mean_diff_bug)Hm, we are not getting a valid histogram. Let’s now go down the function nesting to insert a browser() call in one_sim:

one_sim_bug <- function(n, control_prob, rel_effect) {

browser()

treat_prob <- control_prob / (control_prob * rel_effect)

cy <- rbinom(n = n, size = 1, prob = control_prob)

ty <- rbinom(n = n, size = 1, prob = treat_prob)

mean(ty) - mean(cy)

}

mean_diff_bug <- rep(NA, n_sims)

for (i in seq_along(mean_diff)) {

mean_diff_bug[u] <- one_sim_bug(n = n_obs,

control_prob = control_prob,

rel_effect = rel_effect)

}When we do this, we can find that we incorrectly divide control_prob by (control_prob * rel_effect) the ultimate result, is that the output of one_sim is NA. We can’t create a histogram of NAs. Once we solve this issue, we should get the expected histogram.

🥅 Exercise

A. Replicate the example above. This time use Monte Carlo simulation to find the distribution of p-values if you had a total sample size of 2,000. Hint: extract p-values in R from a t-test with t.test()$p.value .

“Extra credit”: how often would you incorrectly reject the null hypothesis of no difference of means at the 95% level with total sample sizes of 1,000, 2,000, 10,000, and 100,000? Plot the proportion of simulations falsely rejected across these sample sizes.

B. Imagine that we are interested in understanding how bad confounding by an unobserved variable could be in a DGP:

\(Z\) is a confounder. It causes both \(X\) and our outcome of interest \(Y\). Imagine we couldn’t observe \(Z\). Create a Monte Carlo simulation to explore how this confounder could be biasing our estimate of the relationship between \(X\) and our \(Y\).

Assume a data generating process described by:

\[ Z \sim \mathrm{Binomial}(0.5)\\ X \sim \mathrm{Binomial}(0.8 - 0.6 \cdot Z) \\ \epsilon \sim \mathrm{Normal}(0, 1) \\ Y = X \cdot 1 + Z \cdot 3 + \epsilon \]

How different is the estimated effect of \(X\) on \(Y\) when we include the unobserved confounder compared to when we don’t include it?

Hints: use lm() to estimate a linear model. Coefficients can be extracted from lm model objects, say m1 with m1$coefficients.

Extra credit: how does this impact change as you vary the relationship between \(Z\) and \(X\) i.e. change \(0.6 \cdot Z\)? Answering this question will likely take some programming beyond what we have covered so far. Google is your friend here.

Extended pair project: Option 1

Propose a data generating process and two estimation strategies for a quantity of interest from this DGP related to work that you are interested in.

Create “acceptance criteria” to decide it which estimation strategy is more promising given this DGP.

Conduct Monte Carlo analysis of the estimation strategies and determine what is the best estimation strategy.

Extended pair project: Option 2

This project requires significant additional Googling/questions for the instructor, but you will learn the valuable skill of creating R packages. R packages are a great way to wrap up reusable code, share this code with others, and ensure it has a high quality, for example by building in automated testing.

In this pair project:

create an R package from the functions in this example. Hint: in RStudio click

New Project. . .->New Directory->R Package.ensure the functions are well documented using the function documentation syntax above.

create examples and automated tests to ensure that the functions run correctly using the

testthatpackage. Hint: install the usethis package and, within your package’s R project enter the functionuse_testthat().

A great resource for R package creation is Wickham and Bryan’s R Packages.

References

This example is modified from Gelman, Hill, and Vehtari (2021 Ch. 5, p.69-70).↩︎

We can express this in R using scientific notation, e.g.

2e6.↩︎These conventions are established by the roxygen2 package. If you create an R package to contain your functions, you can use roxygen2 to automatically generate package documentation. For more details see R Packages.↩︎

If you ever need to kill an R process (e.g. because it is taking way longer than you expected, use

Ctrl + cin your R console.↩︎replicate()is a wrapper forsapply()you can see how this code works by typingsapplyinto your R console.↩︎Note that there is random variation in computation time. So if you want to get a more accurate sense of computation time use the microbenchmark package. This does repeated runs of the call and reports the distribution of run times.↩︎

See the Wiki page on debugging for a visual example of an early computer bug, an actual bug that got stuck in a computer.↩︎